… As for the bridge on the River Kwai, it crossed the river only in the imagination of its author.

(Ronald Searle, To the Kwai and Back: War drawings 1939–45, 1986)

I traveled to find the Bridge on the River Kwai, and it wasn’t there

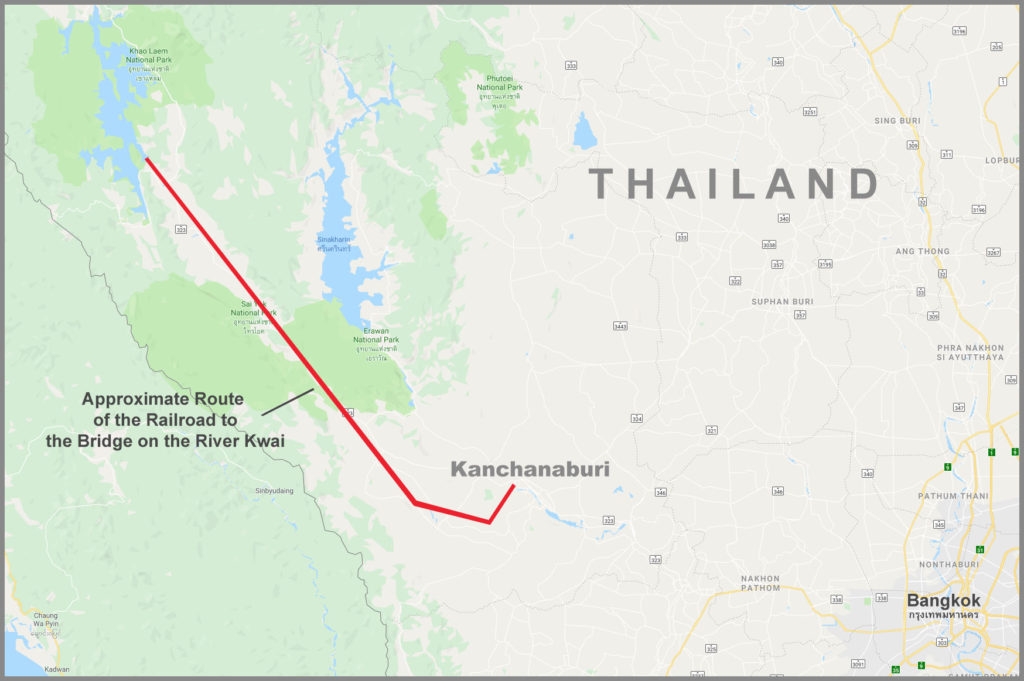

We took a bus to Kanchanaburi, Thailand (about three hours north of Bangkok, near the border of Myanmar), largely because I wanted to visit the bridge on the river Kwai. This was the first of several trips I’ve taken to check out film locations for some of my favorite movies, and The Bridge on the River Kwai was one of them. Our journey to Kanchanaburi was begun in the days when we were the only non-Thai travelers on the bus (in the early 1980s), and no one spoke English. All signs were incomprehensible to us, so we fervently hoped that we would end up in Kanchanaburi.

We traveled to Thailand before the advent of the Internet, and so we did not know the extent to which Kanchanaburi was already well established as a tourist zone. Stalls lined the road, with mugs, t-shirts (yes, dear reader, I bought one in pink, with a black train), and other tchotchkes. We fought off some hawkers and made our way to the bridge.

Some background: Axis and Allies during World War II in Asia

During World War II, Allied prisoners of war were forced to build a railway from Thailand (then called Siam) to Myanmar (Burma) so that Japanese supplies and troops could be transported overland.

The terrific heat, lack of food, brutality of the guards, overwork, malaria (among many undescribable illnesses), and bombings contributed to the name “The Death Railway” for this effort. Between 180,000 and 250,000 Southeast Asian civilians and about 61,000 Allied POWs worked on the construction of the railroad. About 90,000 civilians and more than 12,000 Allied prisoners died. The 1957 film The Bridge on the River Kwai is the story about how a bridge was built across the river. More, it is the story of the horrors of war, and, on a personal level, about pride, saving face, cultural clashes, and the impermanence of empire.

Is the Death Railway a Thai holiday destination?

The bridge is located about three km north of Kanchanaburi; it was built over a part of the river then known as the Mae Klong (now the Kwae Yai); it was the second span built there, with a part of the original on display at the Jeath War Museum (named for Japanese/English/Australian/American/Thai/Holland soldiers who were POWs imprisoned there. Jeath is listed as “the oldest of all Death Railway-related museums in Kanchanaburi, Thailand” (a dubious honor?) on the Dark Tourism web page. And Lonely Planet notes that “war cemeteries, museums and the chance to ride a section of the so-called ‘Death Railway’ draw numerous visitors to Kanchanaburi.”

Note to Self: films are fiction, not real life

I soon found out that the film Bridge on the River Kwai was actually shot in Sri Lanka. In fact, the bridge in Kanchanaburi doesn’t resemble the one in the film at all; it is made of steel and is sturdier and larger than the one built by the POWs. The Kwai bridge would never had survived the war had it been built of local timber and stone, largely because it could not have survived the monsoon season.

Some sources say that the real bridge was built of wood and was about 330 ft. upriver from the one that tourists visit. The wooden bridge was rebuilt in 1945 when Allied troops bombed the iron bridge. No remnants of the wooden bridge survive.

top photo: Crowds travel the 300m-long walkway over the “Bridge on the River Kwai,” a major tourist attraction as well as the site of a working railway.

The Bridge on the River Kwai and its place in film history

In 1999, the British Film Institute voted The Bridge on the River Kwai the 11th greatest British film of the 20th Century, although three of director David Lean’s films scored higher—Brief Encounter (1945), Lawrence of Arabia (1962), and Great Expectations (1946). The Bridge on the River Kwai lacked the illicit romance of Brief Encounter and the Charles Dickens source material of Great Expectations, but for thrills, drama, and a dive into personality flaws on a grand scale, Lawrence and Bridge are pretty comparable, especially vis-à-vis tough questions about the moral, cultural, and military reach of the British Empire.

The origins of the film

For those readers who haven’t seen the film The Bridge on the River Kwai (1957), I urge you to watch it immediately. Based on the 1952 novel Le pont de la rivière Kwaï (The Bridge Over the River Kwai) by Pierre Boulle (who also published Planet of the Apes in 1963), Kwai won—among many other honors—seven Academy Awards, including ones for Lean, Alec Guinness (who played Lt. Col. Nicholson), and the top award for best picture in 1958.

Script credit to a man who spoke no English

The only other actor nominated for an Oscar for his role in the film (as Col. Saito) the great Japanese star Sessue Hayakawa, did not win the award. Boulle received sole screenplay credit (although he did not speak or read English); uncredited were the actual writers Carl Foreman and Michael Wilson, drummed out of the credits because they were on the House Un-American Activities Committee blacklist when the film was released. (They were finally given credit for the film’s script in 1984, in a special Academy ceremony.)

When the Legend Becomes Fact: Print the Legend

Nicholson is easily the most compelling—and ultimately horrifying—character in the film. As Philip Roth wrote in a film review for the New Republic magazine in 2011, for Lt. Col. Nicholson, “the bridge becomes his Moby Dick.” Roth also noted that the Lt. Col. was “obsessed, first, with constructing a monument to British ingenuity and determination; then with keeping his men well-disciplined and spirited; and finally with remaining a model officer….that the bridge will finally be a strategic link in the Japanese railroad system from Bangkok to Rangoon does not, cannot, concern him.”

In the same way that the Kwai bridge in the film was not the Kwai bridge over the Kwae River and the site of filming in Sri Lanka was not the site of the action in what is now Thailand and Myanmar, Alec Guinness’ character was far from the man upon whom his was based.

The real hero of the story

Lt. Col. Philip Toosey was the senior officer in the POW camp at Tamarkan in Thailand during the time that Bridge 277 of the Burma Railway was constructed. In the film, Nicholson helped the Japanese build their bridge, whereas in reality the Japanese were skilled engineers and surely did not rely on him for his planning services.

Nicholson eventually collaborated with the enemy in the film by insisting on overseeing the completion of the bridge because of his own pride and misdirected ideas of honor. According to BBC journalist Paul Coslett, Toosey made every effort to sabotage and delay the building of the bridge. In the book The Man Behind the Bridge: Colonel Toosey and the River Kwai (1991), author Peter Davies interviewed survivors about how Toosey’s major concern was ensuring that as many of his men as possible survive captivity. Many of the survivors were angered that audiences might remember their commander as a someone who worked for the enemy.

“What a human should be”

When the war ended, Toosey spoke on behalf of Col. Saito, who was second in command at the camp and was thought to have been more humane in his treatment of the POWs. As a result, Saito was never tried for war crimes. Toosey and Saito eventually developed a bond based on mutual respect, according to Toosey’s family. (See The Colonel of Tamarkan: Philip Toosey and the Bridge on the River Kwai [2005] by Julie Summers, Toosey’s granddaughter). In 1974 Saito visited Toosey’s grave and sent a letter to his family, saying that Toosey had shown him “what a human being should be.”

The horrors of war illustrated

Bridge 277 took the POWs eight months to build. Many of the dead were buried in several cemeteries in or near Kanchanaburi. Others bodies were simply thrown into the river. Survivors were sent to the notorious Changi prison in Singapore. Some 200 more of them died of disease at that prison. Those who lived were forced to build an airfield for the Japanese. In 2000, a compensation agreement created by the British government gave those who returned from Changi 76 British pounds (less than $100) for their ordeal.

By the way, the late and well-known satiric artist Ronald Searle, the source of the quote at the beginning of this article, chronicled his story of Changi and of the Death Railway. He wrote and illustrated the book To the Kwai and Back: War Drawings, 1939-1945 (1986), which documented the savagery and depravity of working on the Death Railway and his time at Changi, where ninety-five percent of all inmates died. The old prison at Changi was demolished in 2000.

Changi prison on film, far from Asia

I didn’t particularly want to go to the historic site of Changi in Singapore. Good thing, because although it was the location of the 1965 film King Rat—another great film (and based on the novel by James Clavell) about POWs during World War II—it was shot entirely in California.

Please check out these great books and films on Amazon.com.

The Bridge on the River Kwai (film)

Lawrence of Arabia

Brief Encounter

Great Expectations

The Bridge Over the River Kwai (book)

Planet of the Apes (book)

Moby Dick (book)

The Man Behind the Bridge: Colonel Toosey and the River Kwai

The Colonel of Tamarkan: Philip Toosey and the Bridge on the River Kwai

To the Kwai and Back: War Drawings, 1928-1945

King Rat (film)

King Rat (book)