War vs the Spanish Flu

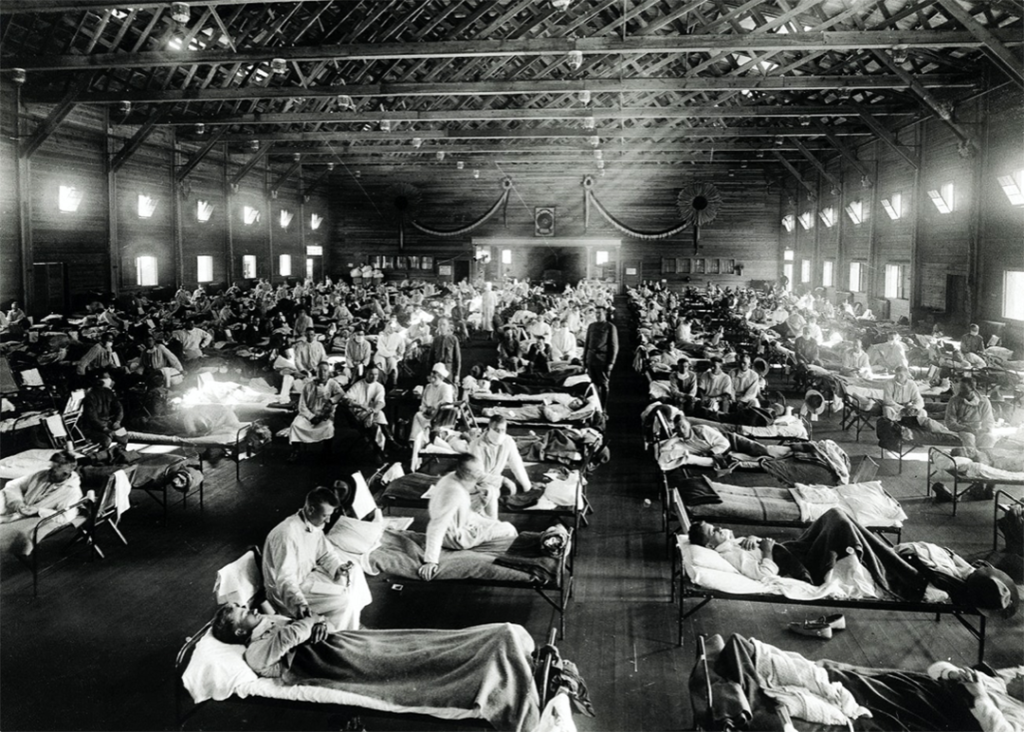

The Spanish flu struck down soldiers and civilians alike at the end of the second decade of the 20th century. In fact, the Spanish flu pandemic of 1918 infected some 500 million people around the world and killed an estimated 20 to 50 million victims.

Millions of the soldiers killed in World War I were young, and it was also true that those hardest hit by Spanish influenza were between the ages of 20 and 40, at the prime of their lives.

The Drama of War

For many writers of the era, war seems to have been the central experience of their lives. There was drama, there was suffering, and there was heroism.

But why didn’t the great writers of the early 20th century, writers like Hemingway, Dos Passos, Ford Madox Ford, and F. Scott Fitzgerald write about the Spanish flu pandemic that killed more people than would die on the battlefields of World War I?

After all, individuals and families in the U.S. and abroad faced threats as dire as those faced by brave men on the front lines. Was their story any less compelling?

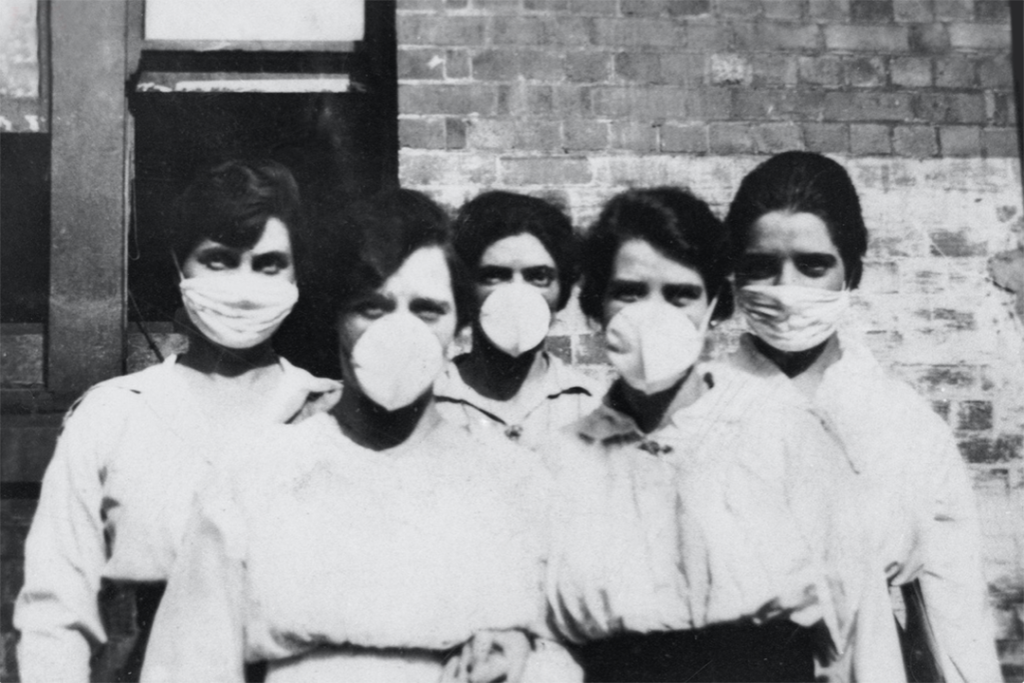

Influenza: Wartime Censorship and Denial

“They terrified by making so little of it, for what officials and the press said bore no relationship to what people saw and touched and smelled and endured. People could not trust what they read.”

The Great Influenza: The Story of the Deadliest Plague in History (2004), by John M. Barry

Other than newspapers, which vastly underreported news about the pandemic, there was little written about the Spanish flu at the time. It was years before there were literary attempts to dramatize accounts of what this tragedy did to generations of families.

Lives Locked Down

Governments took over radio activities during World War I and suspended civilian radio broadcasts. Travel writing came to a halt both because of the war and because of fears of disease transmission. Borders closed; many believed that immigrants would carry disease between countries. Planes and cars were largely unavailable to the masses, and, although trains and ships were the most popular form of travel at the time, both were taken over by the need to move troops and other personnel during the war. There was little news about—and therefore little preparation for—a world-changing pandemic; it was no wonder that the Spanish flu was largely ignored by the larger world.

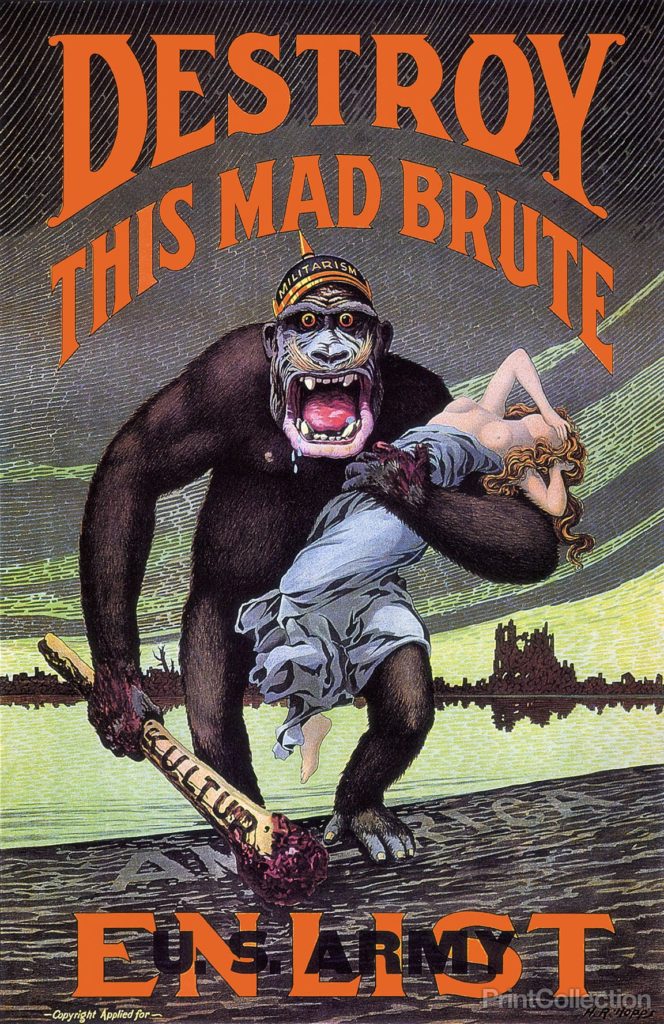

Influenza: Another Enemy

Elizabeth Outka, author of the book Viral Modernism: The Influenza Pandemic and Interwar Literature (2019), thought that one reason that World War I overshadowed the millions of deaths from the Spanish flu was that “the war provided far more compelling enemies, ones that could be seen and put on posters and placed in stories.” The enemy was no longer visible, she writes, “but a silent, nonhuman killer, loyal to no country or creed and able to corrupt the body from within.” It was difficult, she writes, “to characterize a familiar disease like influenza as the enemy.”

The Poets

Turning and turning in the widening gyre

“The Second Coming” (1919), by William Butler Yeats

The falcon cannot hear the falconer;

Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold;

Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world,

The blood-dimmed tide is loosed, and everywhere

The ceremony of innocence is drowned;

The best lack all conviction, while the worst

Are full of passionate intensity.

While Irish poet William Butler Yeats did not name the source of the “blood-dimmed tide” that covered the land, his pregnant wife was a victim of the Spanish flu, and, while most interpretations of the poem focus on the insanity of battle, it has become clear that both Yeats and English writer T. S. Eliot’s lives were battered by this illness and that their poems reflect the horrors that were the result of the pandemic.

Both T. S. Eliot and his wife suffered through the Spanish flu. Eliot’s poem, “The Wasteland,” was published in 1922, but he wrote much of it in 1918 while recovering from the illness. The line “April is the cruelest month” has new depths of meaning when Eliot’s family history is noted, as do the lines in the poem describing the bells rung when new victims of the illness died:

“And upside down in air were towers

Tolling reminiscent bells, that kept the hours

And voices singing

out of empty cisterns and exhausted wells.”

“The Wasteland” (1922), by T. S. Eliot

The Novelists

Other writers were similarly affected by the Spanish flu but many did not name the illness, perhaps because illness, in some way, was thought to be shameful.

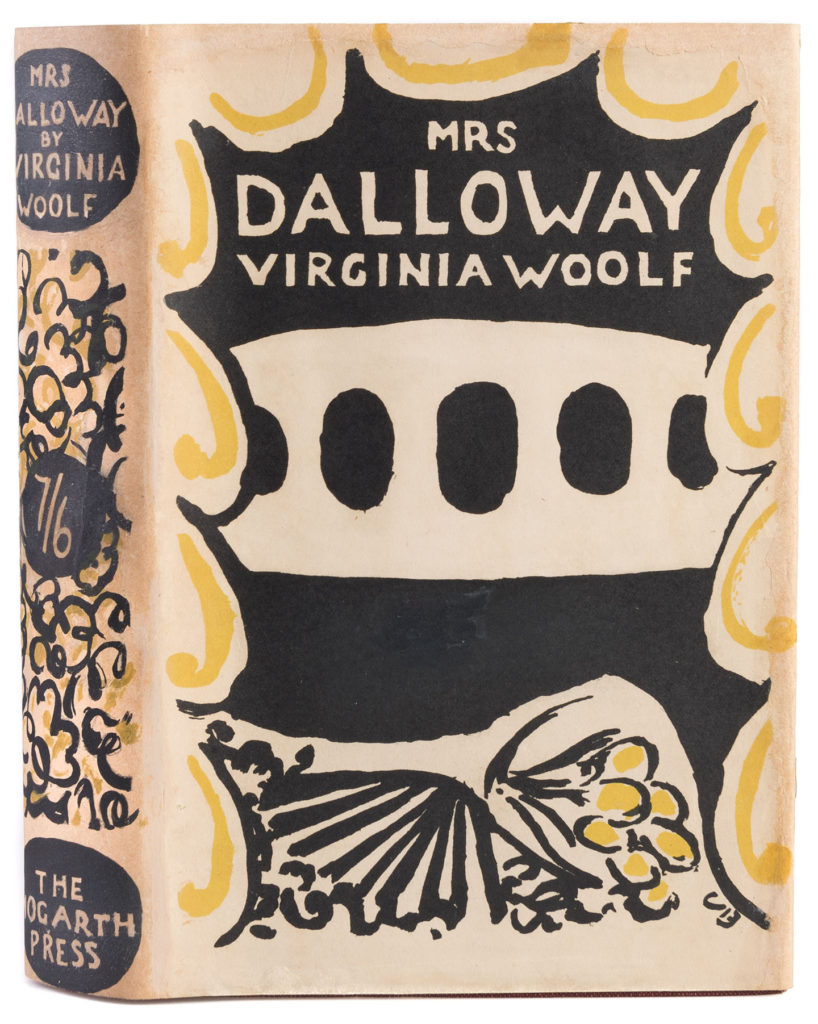

In Virginia Wolfe’s novel Mrs. Dalloway she describes (in her typical lengthy sentences) Mrs. Dalloway’s life after her bout with influenza:

“Silenced she sank easily through deeps under deeps of darkness until she lay like a stone at the farthest bottom of life, knowing herself to be blind, deaf, speechless, no longer aware of the members of her own body, entirely withdrawn from all human concerns, yet alive with a peculiar lucidity and coherence; all notions of the mind, the reasonable inquiries of doubt, all ties of blood and the desires of the heart, dissolved and fell away from her, and there remained of her only a minute fiercely burning particle of being that knew itself alone, that relied upon nothing beyond itself for its strength; not susceptible to any appeal or inducement, being itself composed entirely of one single motive, the stubborn will to live.”

Mrs. Dalloway (1925), by Virginia Wolfe

Woolf’s experience of the Spanish flu also inspired her essay “On Being Ill” (1926), in which she notes that literature is often silent about illness. She writes, “One would have thought that novels … would have been devoted to influenza; epic poems to typhoid; odes to pneumonia; lyrics to toothache,” but she felt that the “perspective of the ill body is absent.”

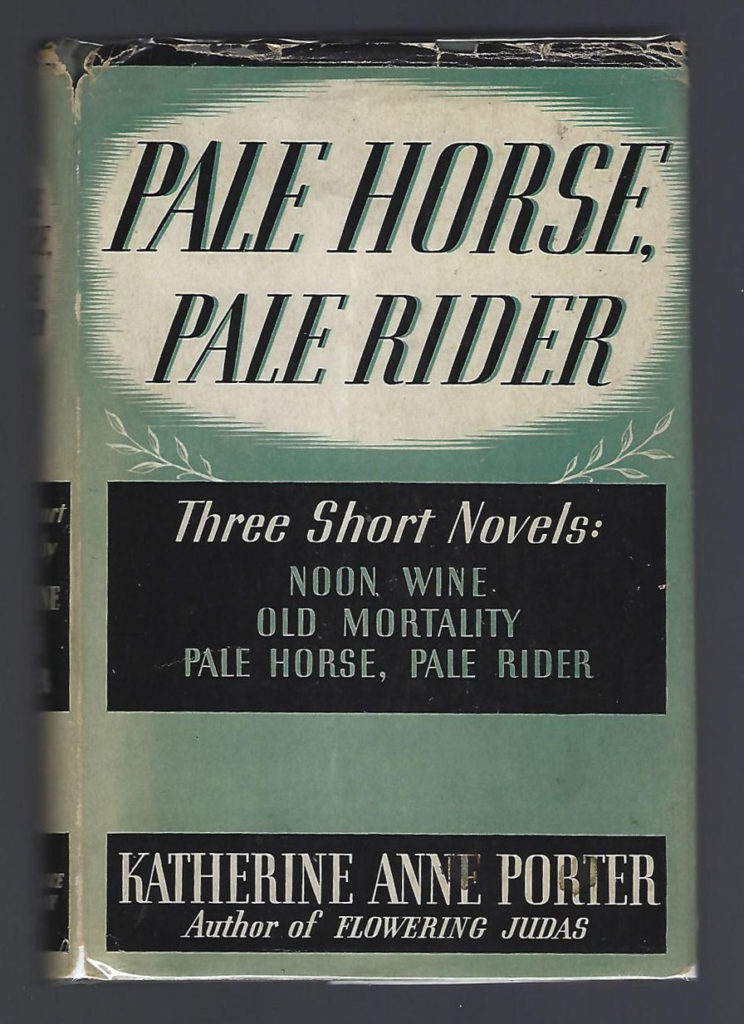

In the title story of American writer Katherine Anne Porter’s collection of three short novels, Pale Horse, Pale Rider (1939), she wrote what was possibly the clearest description of the experience of this illness. In 1918 she was a 28-year-old reporter for Denver’s Rocky Mountain News when she was fell ill with the flu. (Her illness was so severe that her hair famously turned white.) As she describes her protagonist’s experience in the novel:

“Pain returned, a terrible compelling pain running through her veins like heavy fire, the stench of corruption filled her nostrils…; she opened her eyes and saw pale light through a coarse, white cloth over her face, knew that the smell of death was in her own body, and struggled to lift her hand.”

Pale Horse, Pale Rider (1939), by Katherine Ann Porter

The Depth Charge of Pandemics

My family was directly affected by both World War I and by the Spanish flu. My mother escaped poverty and war by traveling across Europe during World War I with her mother and four brothers and sisters (my grandfather had come over earlier). It would take them two years to finally arrive in the United States. Six months later, my grandfather died from Spanish influenza at the age of 33.

I wrote an article for an online journal about my grandfather’s death this past year, largely because the Covid-19 epidemic reminded me of the “depth charge” that families experienced for generations after the Spanish flu struck. The effects that such deaths have had on children, grandchildren, and beyond, is incalculable. My mother lost two young children to polio (within the same week) some 25 years after her father died, another epidemic and depth charge to our family.

While soldiers are often brave, I believe that my family and many others who were challenged by poverty and illness were completely heroic as well, forging ahead after losing a family member or a loved one to illness.

Art is Memory

As a writer, I find it telling that so little was written about the Spanish flu until years later. But in some ways, world events take time to appear in literary works. That may be because Art is often about memory. People continue to write and make films about events in the past, maybe because they are not able to easily digest the horrific stories of illness and death from the pandemic until years later.

Will Art Come Out of Our Terrible Times

The Spanish flu pandemic shaped the modern world in different ways than did the Great War. Like the war, it bent and changed world politics, family structure, medicine, and the arts. But it was also an invisible enemy, one that could not be fought with guns or bombs.

Today more people are interested in what happened during those dire pandemic years, perhaps because we are experiencing something comparable in a world challenged by Covid-19. It may be years before the full effects of Covid-19 are digested by artists and writers and made into Art.

I’ll check it out. Many thanks for letting me know—

Best,

Barbara