Part I: Curiosities

It all began at the venerable Strand bookstore near Greenwich Village in New York City in 1988. I was perusing a pile of new books stacked on a table and came across a book about off-the-beaten-path places to visit. As I flipped through the pages, I saw it: Mr. Potter’s Museum of Curiosities in Cornwall.

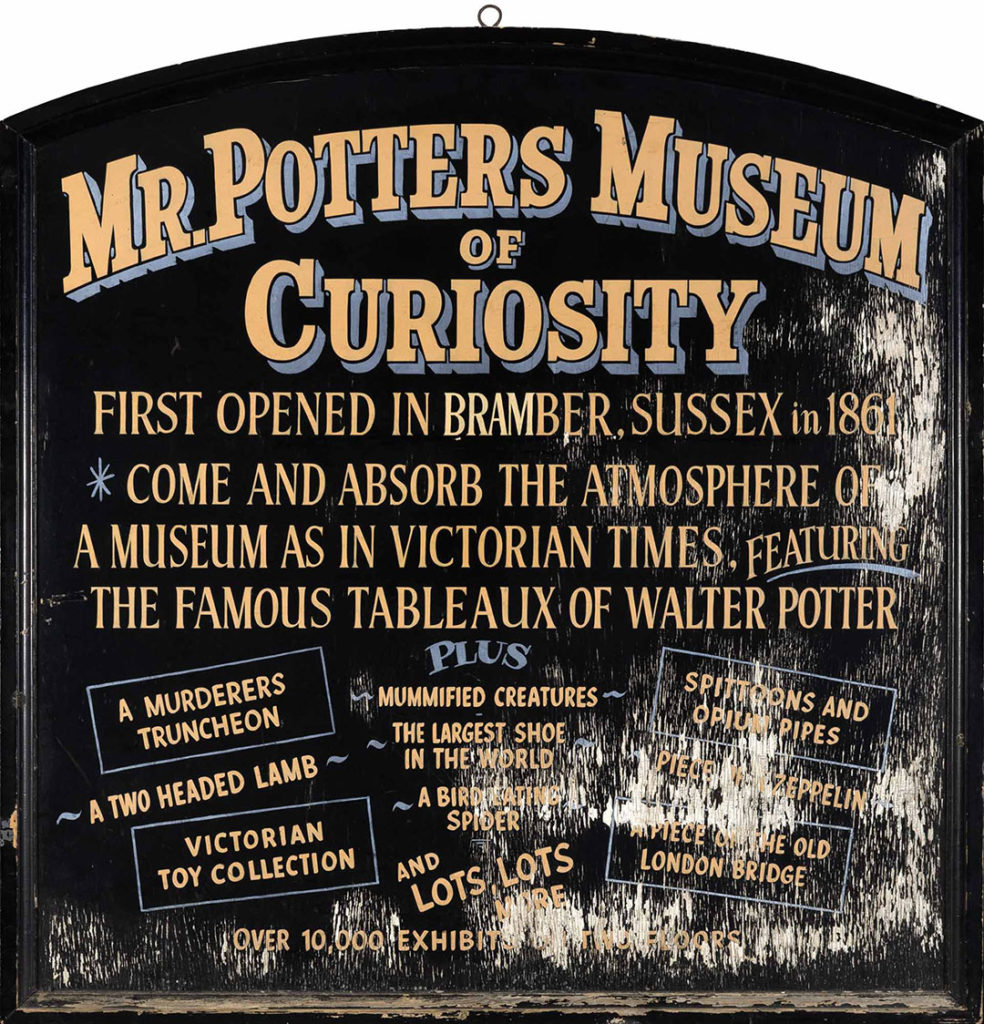

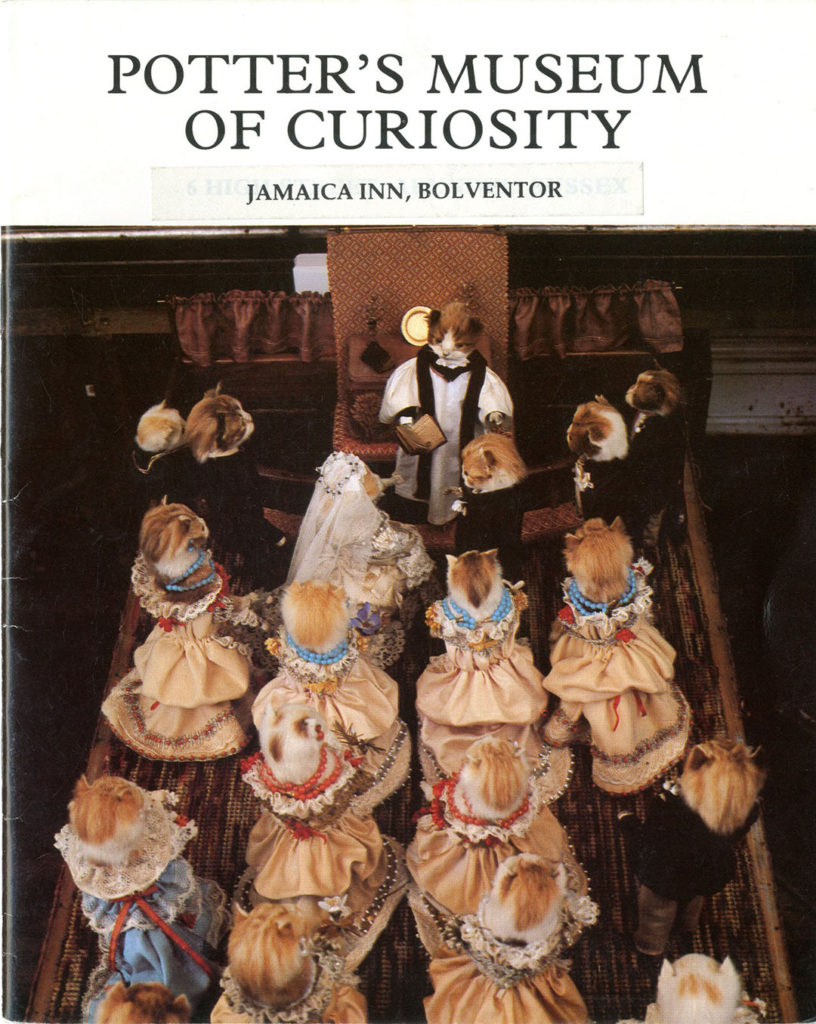

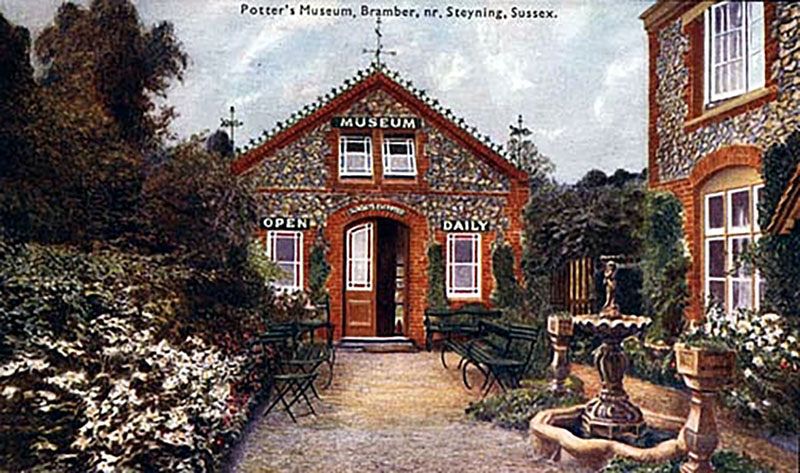

(Note: the original name was Mr. Potters Museum of Curiosity when it opened in 1861 in Bramber, Sussex. The museum was sold in 1984 to the owners of the Jamaica Inn in Bolventor, Cornwall, where it remained a popular destination until its contents were auctioned off in 2003.)

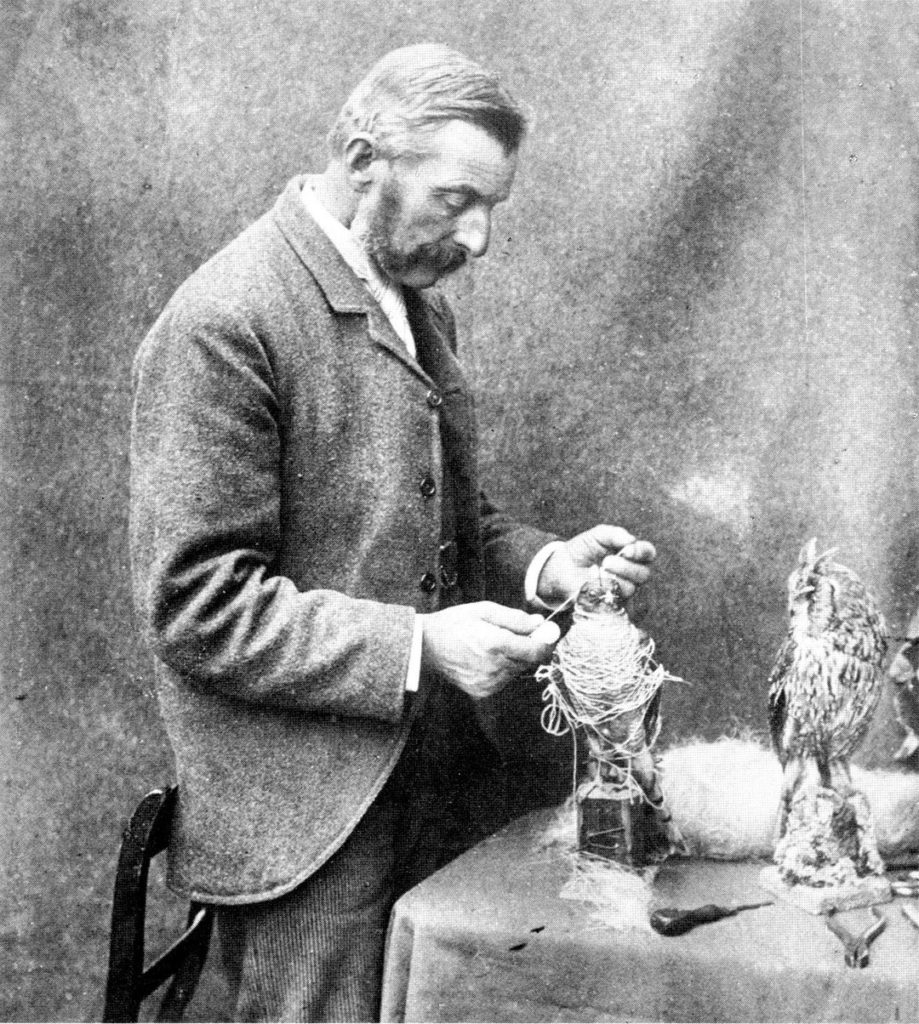

The story of the museum hooked me: In the 19th century Victorian taxidermist Walter Potter created tableaux of kittens, frogs, bunnies, and a marching band of mice, along with other small animals—all posed as if in a British children’s story or poem. The creative taxidermy found at Walter Potter’s Museum of Curiosities represented, as one wag put it, the “merging of kitsch and morbidity” prevalent in Victorian times. A visitor wrote that Potter’s pieces seemed to be “conjured by Beatrix Potter during an acid trip.”

It seemed just the ticket for a unique way to surprise my boyfriend, although I wasn’t sure about his response to the two-headed lamb mentioned in the book.

Victorian Taxidermy: Kitsch and Morbility

From what I read, the museum was doing a brisk business in the last two decades of the 20th century. This was not surprising, since taxidermy has a long history in the United Kingdom. To the public of the mid-19th century, these departed animals stuffed, dressed, and posed as if in a schoolroom, a drawing room, or a cricket match were considered both art and entertainment. In the great British Exhibition of 1851 taxidermists showed their work to an enthusiastic public. (For anyone who has visited the American Museum of Natural History in New York City or scores of other museums, dioramas of taxidermied animals in their habitats are favorite places for kids to explore).

London Surprise

I was pretty sure that my boyfriend Martin would be just as enthusiastic. Not knowing the destination I had chosen, he met me in London, where he had just arrived after a trip with his father in Poland. His father was of Polish ancestry, and their journey involved much socializing with relatives, accompanied by lots of toasts and platters of heavy food.

Martin’s insides were shaky by the time he arrived at Heathrow, where I had rented a car for our journey to Jamaica Inn in windswept Bodmin Moor in Cornwall. I did not plan to tell him about the museum, “It is a surprise,” I said.

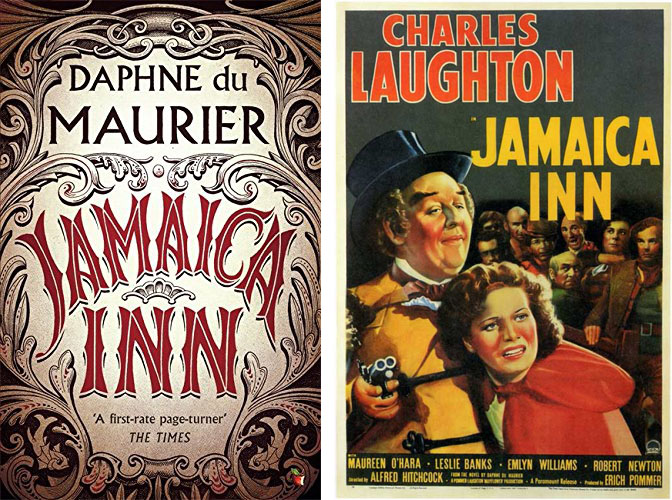

Jamaica Inn, built in 1750, is located on the Cornish coast about a half hour from the ruins of Tintagel Castle, famous for its links to the legend of King Arthur and his Knights. Jamaica Inn itself is a place of vivid myths and legends, of smugglers and pirates, reported paranormal activities. There are even stories of a mysterious creature nearby, the Beast of Bodmin.

Legends and Lore: Jamaica Inn

The name of the inn originated with the local landowners, members of whose family were governors of Jamaica in the 18th century. Daphne Du Maurier, who was said to have stayed in the inn in 1930, was inspired to write the popular novel Jamaica Inn (1936) about crime and the power of evil—all faced by a bold young heroine in the most desolate of landscapes and in a place still thought to be haunted. The memorably moody 1939 film thriller based on Du Maurier’s novel was directed by Alfred Hitchcock and starred Maureen O’Hara, Robert Newton, and Charles Laughton. Du Maurier’s other works include Rebecca (1938), My Cousin Rachel (1951), and others.

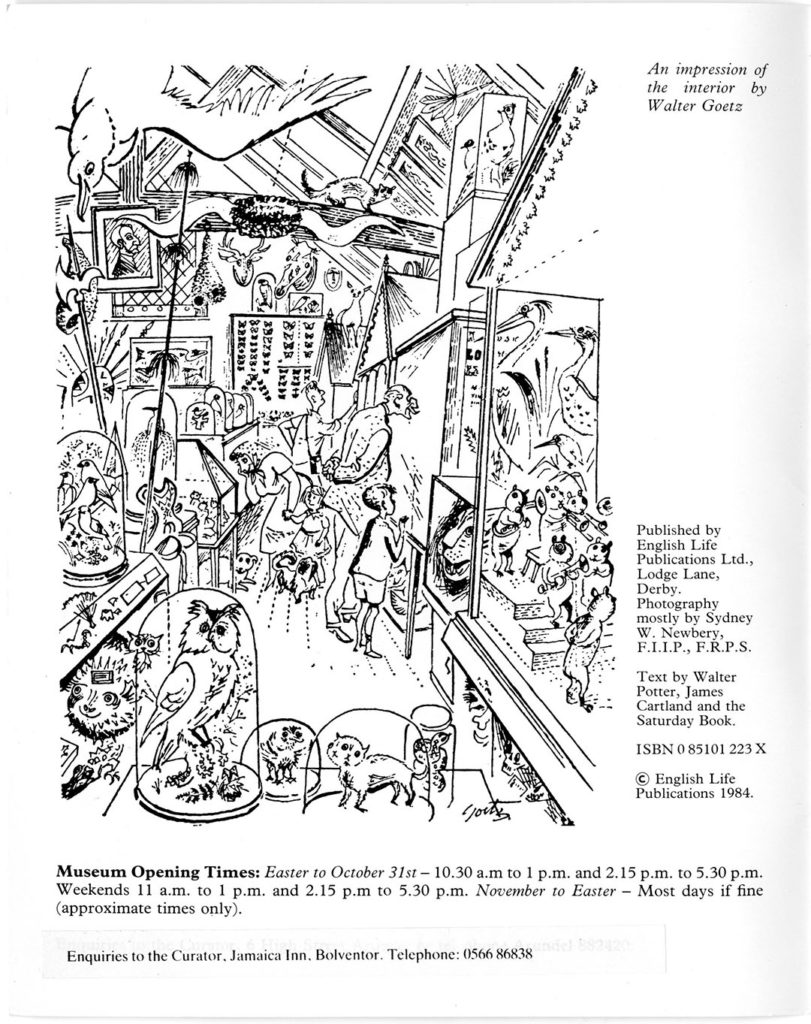

Dark clouds were hanging over the site when we visited 35 years ago, but they dispersed with the arrival of busloads of tourists from all over England, clattering into the restaurant for tea. Those entering the inn were greeted by a large and colorful parrot (unstuffed) in a cage by the door. The restaurant was filled with elderly British ladies on a trip to visit the curiosities.

Pretty Birdie

I remember when a very Monty-Pythonesque elderly soul in front of us got up close to the parrot and whispered, “Hello, pretty birdie.” The parrot answered: “F**k you, dear!” There was a pause, and the sweet old lady said, “F**k you too!!” I thought that this exchange was worth the journey, but there was more to come.

Who Killed Cock Robin?

We began to walk through the dark exhibit spaces, and it didn’t take Martin long to turn green. The first window we came to revealed Potter’s famous tableaux: “The Death and Burial of Cock Robin” (1861), which took seven years to complete. It was based on the children’s poem, “Who Killed Cock Robin” (1774). The following verses encapsulate the feeling of the poem:

“Who killed Cock Robin?

I, said the sparrow,

with my bow and arrow,

I killed Cock Robin.

Who saw him die?

I, said the magpie,

with my little teeny eye,

I saw him die.

“Who caught his blood?

I, said the duck,

it was just my luck,

I caught his blood….”

Potter was inspired by the poem in 1854 and set to work on his storehouse of specimens. Almost 100 English birds later, Potter unveiled “Cock Robin” at his parents’ inn, launching the dream of his museum. Meticulously clothed and stitched, a few of the avian mourners actually shed glass tears. In 2003 “Cock Robin” was sold for £23,500 in an auction at Bonhams in Chicago.

Ethical Taxidermy, Sez Potter Fans

While “Cock Robin” and other pieces in the museum would probably be thought horrific by Americans, Potter’s British fans described his work as “ethical taxidermy,” since he said that he did not kill animals for his dioramas and many of the cadavers were brought in by visitors who had found them dead. It seemed pretty suspicious to me that all of those dead kittens piled up just at the right time.

Kitty Galore

But by then Martin was not concerned with the source of the dead animals for the tableaux; he was concerned with breathing fresh air and seeing the sun (but good luck to him—it was the UK). He quietly found an exit, but I moved on to another high (or low) point at the museum, a giant Potter creation titled Kittens’ Tea & Croquet (1890). This one consisted of 37 kittens, 17 seated for dinner and the others playing croquet.

The piece was later exhibited in 2001 at the Victoria & Albert Museum in London in a special exhibition titled “The Victorian Vision: Inventing New Britain,” with a book/catalog published the same year. Located in an annex devoted to taxidermy, the piece demonstrated, according to one critic, the “ghoulish worship of death” of the time, representing the popular Victorian trend of making art from animal cadavers. A common hobby during the reign of Queen Victoria, taxidermy was lauded by the Queen herself.

“The Kittens’ Wedding,” another popular scene in the museum, was completed in the 1890s. Among the guests at a wedding party was a disgruntled looking gentleman feline who, it was remarked, resembled Winston Churchill. Many of the birds in the scene were said to be donated by people who found them dead under telephone wires or killed by cats. The tableau sold in 2003 for £21,150 at Bonhams.

Later, in 2016, “The Kittens’ Wedding” was exhibited at Brooklyn’s Morbid Anatomy Museum, where it was the centerpiece of an exhibition entitled “Taxidermy: Art, Science & Immortality.” The museum’s co-founder and creative director Joanna Ebenstein (and co-author of Walter Potter’s Curious World of Taxidermy, 2014) noted that “in the 19th century, when most of the pieces in this show were created…taxidermy was seen as a genteel craft appropriate for ladies, with women’s magazines even publishing how-to guides.”

RIP Potter’s Museum, But More to Come

Certainly the art of taxidermy has lost many of its practitioners after the Victorian era. According to a recently-published history of taxidermy, there were 369 taxidermists operating in London alone in 1831. Historians noted that taxidermists of the time were just people doing a job, “like a hair barber or a butcher or a window cleaner.”

Potter’s Museum in Bodmin Moor lasted for less than 20 years, from 1984 until 2003, at which point the exhibit was broken up and auctioned off. American and European bidders offered £529,900 in all, which was more than twice the expected amount. Artist Damien Hirst had offered a million pounds to keep the collection intact, but he was too late. The pieces were distributed to high bidders and now live in the homes of an enthusiastic group of Potter aficionados.

(Note: I wrote this blog more than 30 years after I visited the museum, and now I find myself barely able to look at photographs of Potter’s creations without feeling ill. My husband Martin [who loves horror films], agrees).

This is such a great recollection of your bizarre visit to such a bizarre museum! Very entertaining and well written story. Just reading it made me feel as Martin did.

You could not pay me enough to see those displays. I’m always uncomfortable at the natural history museums.

But I really like your story, so I guess I’ll have to read Part II. I always enjoy your writing.

Thanks, Joan: Glad that you liked it. Is a kind of queasy topic for a lot of folks. I’ll have to write Part II now because I have one fan lol.